Steve Witkoff is Under the Influence

It's not just Trump. Real estate developer turned ersatz foreign policy negotiator Steve Witkoff's ties to Russia are just as compromising.

“Al! How ya’ doin’?”

“I think your father’s in the Jewish mafia,” Nina murmured. My dad, his girlfriend Nina and I were having dinner at Rao’s, the Italian restaurant in East Harlem now famous enough to slap its name on a nationwide brand of frozen lasagna and jars of tomato sauce.

Rao’s was known as a Mafia hangout, and scenes from the movie Goodfellas were filmed there. When we drove up to East Harlem, my dad would point out the car window and tell me to notice how clean the streets were between 113th and 116th. The garbage was picked up assiduously. There was no crime on those blocks. Street crime, that is.

I don’t know if my dad ever ran into Steve Witkoff, who was a Rao’s regular, one of what we’d now call a posse: ex-cop-turned-celebrity Bo Dietl, a jeweler called Mike the Russian, clothiers Sheldon Brody and Joseph Abboud, and the singer Paul Anka.

I am pretty sure my dad, who was an advertising guy, wasn’t in the mob. But in those days, it seemed as though everyone in New York was Mafia-adjacent. Certainly in real estate, the Mob was ubiquitous. You couldn’t do business without them. We’re talking building trades, garbage collection, that stuff. For Jewish guys from the boroughs who tended to be smart but short in stature, mobbed-up swagger had appeal. So it was with Witkoff, who kept a copy of the book Tough Jews on his desk, according to a profile in The Observer by Devin Leonard.

I read most of Tough Jews. It wasn’t the melodramatic recitation of Jewish gangsterism in the ‘20s and ‘30s that I had expected. Nostalgia, not bullets, shot through the pages. The story is one of immigrants who came to the U.S. with nothing but anger bred by hardship and disenfranchisement, and their sons, Jewish men who felt they had to prove their masculinity against a stereotype of frail bookishness.

Bronx-born Steve Witkoff channeled that requisite toughness, even though his family had ascended to the middle class on Long Island. After earning a law degree from Hofstra University, working for a firm that represented Donald Trump, he caught the real estate bug. A decade younger than the publicity-seeking developer, Witkoff wasn’t turned off by Trump’s braggadocio or the crassness that evoked contempt from old line New York and made Trump a target for Spy magazine satirists who dubbed him “a short-fingered vulgarian.”

"He'd come to 101 Park Avenue, where I was a lawyer,” Witkoff told a reporter. “He had this swashbuckling style. I used to see him come in and I used to say, 'God, I want to be him.'"

According to David Breger, a retired attorney active in New York real estate who got to know Witkoff, the younger man wasn’t always as admiring as his comments to the press suggest.

"When I did closings with Steve in his first days, and we would sit waiting for wires to hit, Steve would amuse the table with stories of Trump chutzpah, stupidity and bad business judgment. There’s a sizable cohort of NYC real estate guys who thought the Dotard was a joke, and now they hold fundraisers for him."

Perhaps Witkoff could be forgiven for a certain acerbity. Unlike Trump, the spoiled scion of his father’s real estate empire, Witkoff didn’t come from money. Borrowing $20,000, half his father’s life savings, he started small, buying distressed apartment buildings with a partner in Inwood, the farthest north you could get and still be in Manhattan. Witkoff appears to have been, as the book title goes, a tough Jew, packing heat to deal with recalcitrant tenants and when money was tight, he reportedly dug trenches and did his own plumbing.

Now Steve Witkoff is a billionaire, sobered by time, and, perhaps, grief. In interviews, he comes off as mild, reasonable, and even compassionate, a stark contrast to Trump. Yet he became one of the Trump’s most loyal friends, perhaps the only real friend of the notoriously transactional president. Witcoff speaks warmly of how Trump was there for him after his son Andrew died at 22 of an Oxycontin overdose. For his part, Witkoff testified on Trump’s behalf in his 2023 fraud trial, and he was one of the few Trump associates whose support was not shaken after Jan. 6. His loyalty is to Trump, not MAGA, but while he’s not ideological, his politics are those of a right-wing businessman.

As it turns out, Witkoff may have succeeded in emulating Trump in more ways than one. Now, questions are being raised about Witkoff’s ties to Russia, as well as conflicts of interest that mirror Trump’s.

Those questions lead to one man, someone far better educated and more cultivated than Witkoff, and certainly more urbane than Trump: Leonard Blavatnik. The Ukrainian-born Blavatnik is known as the richest man in England, a philanthropist who has left his mark at Oxford University and Harvard, and a man who became impossibly rich in the notorious “aluminum wars,” the bloody asset grab that created a class of Russian oligarchs after the breakup of the former Soviet Union.

Not Your Father’s Oligarch

Blavatnik is not your everyday Russian oligarch.

Born in Odessa to a Jewish family, Blavatnik emigrated to the U.S. to attend graduate school in 1978. Like many men who made fortunes in the Wild West days after the breakup of the Soviet Union, Blavatnik is well-educated, but because of his U.S. citizenship, his resume is more impressive than most: a master’s degree in computer science from Columbia and an MBA from Harvard. He didn’t face the hardships of post-Soviet Russia; instead he worked as a computer programmer at Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York while men like Oleg Deripaska, now a multimillionaire, hauled bricks on construction sites and wondered where his next meal was coming from.

Now in his 60s, Blavatnik emanates the sleekness and gravitas of a man with a fortune estimated at more than $30 billion and a knighthood. An art collector and major funder of museums, cultural institutions, and universities, Blavatnik was made a chevalier of the French Legion d'Honneur in 2013 for his contribution to the arts and education in France. His philanthropy is wide-ranging, but the universities stand out, including massive donations to Harvard, Yale, and Oxford, where he funded the Blavatnik School of Government. More on that particular donation later.

Where does the money come from? That’s a less elevated story. As state industries were being privatized, Viktor Vekselberg, Blavatnik’s classmate from his undergraduate days in Moscow, convinced him to return to Russia. Along with Oleg Deripaska, who had studied theoretical physics and economics, these smart young men on the make saw opportunity in the chaos of the post-Soviet era.

These were rough, violent days in Russia. The magazine EuropeanCEO called the scene “a blood-soaked asset grab.” From the chaos: “a few dozen oligarchs emerged – and several potential oligarchs lost their lives.”

“As the state began to sell off its resource assets, the size and value of the global market for aluminum, along with the potential for moving money around the globe, attracted such fierce competition that it is estimated 100 people were killed. In the words of Roman Abramovich [who made millions himself in the aluminum wars] ‘Every three days, someone was being murdered.’

Blavatnik was one of those who came out a winner, along with Vekselberg, Deripaska, and Mikhail Fridman. Eventually, the men diversified into oil and Blavatnik’s social skills made him the go-between on an enormous deal with British Petroleum. The resulting company, TNK-BP, became one of the largest oil companies in Russia. In 2013, TNK-BP was acquired by Rosneft, a Moscow-based energy company controlled by the Russian government.

Today, Vekselberg, Fridman, and Deripaska are all billionaires, and all three have been sanctioned, either by the U.S. or the European Union. Blavatnik, by contrast, eased out of Russia, invested in chemicals and plastics (the environment is notable for its absence from his many philanthropic causes) and later, as the very rich are wont to do, invested in the entertainment industry. These days, he owns most of Warner Music.

He’s also invested in real estate.

That’s where Witkoff comes in.

The Odd Couple

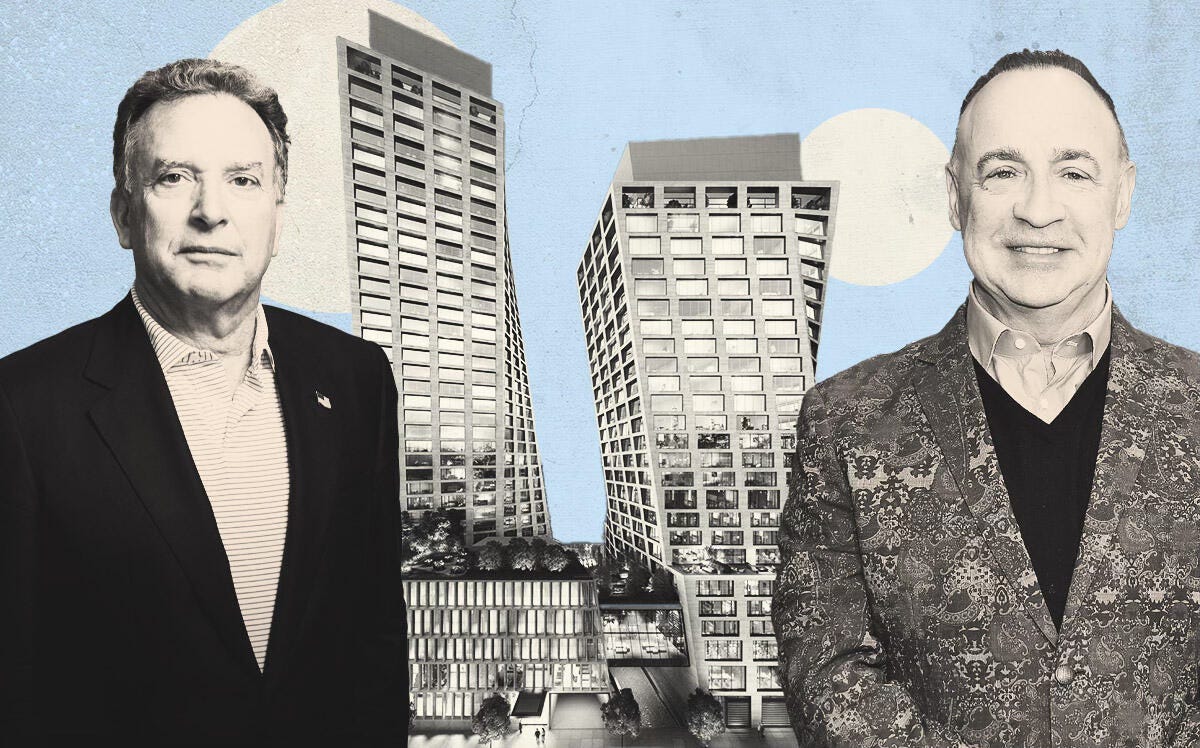

Blavatnik’s Access Industries has an estimated worth of $35 billion, and Blavatnik is said to be the 75th richest man in the world. Witkoff’s net worth is estimated to be a paltry $2 billion, and hearing him speak, compared to Blavatnik, it’s hard not to see them as miles apart in, well, class.

At no time was Witkoff’s lack of knowledge and sophistication more cringe than when he attended a meeting at the Élysée Palace, the 300-year-old seat of the French presidency and one of the great examples of European neoclassical architecture. Witkoff said he was struck by its resemblance to another famous pile, on the other side of the Atlantic.

“You know what this looks like? It actually looks like President Trump’s club at Mar-a-Lago,” he said to the assembled Europeans. “He actually works on it himself. He’s like an architect or a designer.” The remark provoked barely restrained laughter from the other diplomats. But, the Financial Times noted, it also revealed the deep affinity between Witkoff and Trump, described by the FT as “two men who came of age in the white-knuckle world of New York real estate and have been friends for decades.”

In contrast to Witkoff, Blavatnik is, quite frankly, elegant. Yet Blavatnik picked Witkoff out of a crowd and partnered with him on profitable real estate deals. Their companies have acquired properties in New York and Florida, a Chelsea office tower, and resorts in Palm Beach.

Kyiv and its allies have long suspected Witkoff of pro-Russian sympathies. In an interview with Tucker Carlson this spring, Witkoff said there was no reason why Russia would want to absorb Ukraine or bite off more of its territory, and it was "preposterous" to think that Putin would want to send his army marching across Europe.

He also said that Putin “wasn’t a bad guy.”

When Witkoff first started acting as Trump’s foreign policy envoy, there was a sense that he was simply out of his depth. But sources close to Witkoff deny that he has been taken in by Putin. He’s no patsy, as the journalist Samantha de Bendern wrote in an article cleverly titled “The Realtor Who Came in From the Cold.” She quoted the real estate magazine The Real Deal, where a source called him “an animal, a tough New York real estate guy.”

“He’s clear-eyed about who Putin is,” a longtime Trump adviser who has known Witkoff for years told the Financial Times. “But if we’re in a negotiation and I’m publicly shitting on you nonstop, are you more liable to work out a deal with me? No, of course not.”

So why is Steve Witkoff, the tough Jew who carried a piece in Washington Heights, negotiated deals in the ratfuck world of New York real estate, taking it so easy on Vladimir Putin?

Boom and Bust in the ‘90s

The first intimations of possible Russian influence on Witkoff came in the 1990s, go-go years for New York real estate, and a time when Donald Trump’s finances were seesawing, and Trump was selling Trump Tower condos to Russian gangster in need of money laundering. The old WASP families had fled the industry after the stock market meltdown in 1987, and bridge and tunnel guys like Trump and Witkoffwere making bank.

Like Trump, Steve Witkoff got overextended, with foreclosures threatening and a canceled IPO. His main lender, Lehman Brothers, had faced major losses in Russia, and when Witkoff called for a bailout, they turned him down. Somehow Witkoff managed to raise $25 million from what a reporter called “unnamed investors.” With that stake, he persuaded Lehman to bankroll the rest.

Some have raised the question of who bailed out Witkoff. But Witkoff has not received the degree of scrutiny that Trump has, and these are only questions.

There is one documented brush with the Russian mob, when Witkoff wrote a letter of support to a condominium board for Anatoly Golubchik in 2013, reported by Craig Unger, author of American Kompromat.

“In 2013, The Real Deal, a media company that covers real estate, reported that Witkoff had submitted a recommendation for indicted Russian mobster Anatoly Golubchik several years earlier when Golubchik applied to live in a condominium building at 971 Madison Avenue.

“According to indictments in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, Golubchik played a key role in a high-stakes gambling ring based out of Trump Tower, along with Semion Mogilevich, a multibillionaire and one of the most powerful figures in the Russian Mafia who ran drug trafficking and prostitution rings on an international scale.”

He was also accused of selling some $20 million in stolen weapons, including ground-to-air missiles and armored troop carriers, to Iran.” According to an indictment filed by U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara, the gambling ring had been in operation since 2006, if not earlier, and had laundered at least $100 million.

Before he went to jail, Golubchik wanted to purchase real estate in Manhattan. New York condo and co-op boards are notoriously difficult and he needed a personal reference. Witkoff wrote one for him.

The Real Deal published a statement from Witkoff on the letter he submitted for Golubchik. “Mr. Steven Witkoff met Golubchik in 2009 and submitted a recommendation to complete a board package as a favor to a mutual acquaintance,” the statement said. “He knew him tangentially. He regrets providing a reference on his behalf and acknowledges that it was a mistake.”

Unger notes that the statement did not clarify whether or not Trump was the mutual acquaintance.

If nearly every New Yorker was Mafia-adjacent back in my dad’s day, by the 1990s, it seemed as through everyone was Russian Mafia adjacent. As Unger has documented, the Russian and Italian mobs did business together. Witkoff wouldn’t have been oblivious. But was he sophisticated about a different kind of Russian influence?

Soft Power and Subtle Influence

It’s hard not to see Blavatnik’s partnership with Witkoff as an attempt to form a relationship with a bit player known to be close to Donald Trump. Yet Blavatnik strenuously denies being a Putin proxy, and says that he hasn’t seen Putin since 2000.

Russia-watchers are equally strenuous in their allegations that Blavatnik’s massive contributions are serving Putin’s ends with soft power. At least one professor resigned after Oxford University accepted funding for the Blavatnik School of Government.

There has been a similar outcry when Blavatnik donated to other politically influential institutions in the U.S., including The Council on Foreign Relations, which publishes Foreign Affairs magazine. Only the right-leaning Hudson Institute returned one of Blavatnik’s donations. Richard Haas, who headed CFR, refused to do so despite receiving a letter from 56 national security officials, academics, and activists protesting the $12 million donation. The letter stated: “Blavatnik and his fortune cannot credibly be dissociated from individuals and entities who further Putin’s agenda in the U.S. and other democracies.”

The writers added that they were “deeply troubled” by the donation which they alleged Blavatnik gave as part of a longstanding campaign to “launder his image in the West” and “advance his access to political circles.”

A footnote to the letter mentioned the 2013 sale of oil company TNK-BP to the state-owned energy company Rosneft, noting that Blavatnik had reaped an estimated $7 billion and that the deal was orchestrated by Putin and his crony, former deputy prime minister and now Rosneft chair Igor Sechin. (The author euphemistically called a $3 billion overpayment by the Russian government “inexplicable.”)

Vladimir Milov, Alexei Navalny’s chief economic adviser and a former Russian deputy energy minister, told Cherwell, the Oxford student newspaper, that Rosneft paid 40-60 percent over market value to TNK-BP owners Blavatnik, Vekselberg, and Fridman. At the time, Reuters reported that “Putin blessed the deal.”

It’s worth noting that this buyout happened in 2013, long after Blavatnik said he stopped having personal contact with Putin.

Researcher Olga Lautman voiced her take bluntly in a recent phone conversation: “Blavatnik is Putin’s wallet.”

Ilya Zaslavsky, an anti-corruption researcher who heads the free speech organization Underminers, characterized Blavatnik as “a subtle guy” who works as a philanthropist to “subtly shape debates.” While Oxford University has issued statements denying that Blavatnik influenced the eponymous School of Government, Zaslavsky, an Oxford graduate, tells a different story: “Because of his grant, the Blavatnik School of Government invited Putin’s cronies with self-praising lectures and introduced self-censorship on key topics like oligarchs and Ukraine, at least until the full-scale invasion started in 2022,” Zaslavsky wrote to me.

According to the Oxford student newspaper, Oxford’s Said Business School accepted funding from Alfa Bank, controlled the sanctioned oligarch Mikhail Fridman, who has been credibly accused of money laundering. This happened in 2010, the same year the Blavatnik School of Government was founded. Alfa Bank and the business school jointly awarded an Alfa-funded prize to “foreign investors in Russia” deemed to have a “significant positive impact on the community, demonstrated by the size of the investment.”

While the rest of the aluminum wars bros face international sanctions, Blavatnik, by contrast, receives medals from U.S. universities. Author and anti-corruption activist Sarah Chayes characterized Blavatnik’s philanthropy as “image laundering,” a phrase that is very much of the moment. Clearly image is important to Blavatnik. He has threatened to sue journalistic outlets that call him an oligarch, a highly charged term, but Zaslavsky will have none of it.

“He’s a pretty effective oligarch,” Zaslavsky said, “the most clever oligarch of all.”

But Blavatnik isn’t getting off the hook with Ukraine, his birthplace, even though he announced that he had divested almost all of his Russian holdings when it invaded Ukraine in 2022. Investigative reporter Tim Mak’s Counteroffensive reported that in 2023 Ukraine sanctioned Blavatnik at the request of the country’s security services.

Ukrainian officials refused to provide more information, other than to say that sanctions are placed on individuals who harm the state. Ukraine has applied sanctions to other Russian oligarchs: Roman Abramovich, Arkady and Boris Rotenberg and Oleg Deripaska. All are close to Putin.

It is notable that while some people were sanctioned for five years Blavatnik was sanctioned for ten, indicating the gravity of what Ukraine perceives as his impact.

Yet Blavatnik continues to be honored and feted from London to L.A., proof that Len Blavatnik may be not only one of the world’s richest men, but also one of the most effective. Soft power is not to be taken lightly. Remember when Russia was the ultimate enemy? Suddenly, now, U.S. Senators are taking campaign donations from players linked to Putin. Tucker Carlson is singing the praises of Russian supermarkets. And the U.S. president is talking about “Vlad” in admiring tones, at least until recently.

Few have taken the trouble to assess the pervasive and often subtle influence of Putin’s oligarchs. The massive Russian disinformation push to influence U.S. elections has received scrutiny in past years, although seems to have dropped out of the news lately. But disinformation is only part of the equation. It is way past time to bring attention to the masterful wielding of soft power and its pervasive influence on U.S. politics. That includes the influence of Russian money on Donald Trump, dating back to the 1990s, or perhaps even earlier, and the ties to Witkoff, as well. Like Trump, Witkoff meets with Putin without anyone else present, and there is no record of their conversations.

This week, the meeting between Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump in Alaska ended with Trump, once again, selling out Ukraine. Instead of calling for a ceasefire, Trump endorsed the idea that Ukraine should give up territory to the invader - including territory that Russia does not control militarily.

Now, the leaders of the European Union, along with Ukrainian president Vololdymyr Zelenskyy are rushing to Washington to do damage control. But is the damage already done? Perhaps it was done years ago.

Corruption, Inc.

Maybe any possible Witkoff ties to Russia don’t matter. Maybe we should focus on corruption. Witkoff has divested his interest in his real estate firm to his son Alex, but in March, he was still listed as CEO on the company’s website, and has not made ethics disclosures, according to the Revolving Door Project.

Witkoff’s sons, Alex and Zach Witkoff, are co-founders of the Trump family cryptocurrency business, World Liberty Financial. Witkoff himself also reportedly had a hand in founding the business. As of March 2025, Steve Witkoff claimed to be divesting from WLF and transferring his holdings to his sons. According to Reuters, an anonymous source familiar with Witkoff’s plans stated he would place his assets in a blind trust but would retain ownership.

Ethics experts contend that even with a trust, conflicts of interest could arise if his financial stake in World Liberty benefits from his diplomatic role.

In addition, Witkoff has long-standing business ties to Gulf state sovereign wealth funds. These wealth funds are one of the biggest sources of investment for real estate properties in the United States. According to the New York Times, “For Mr. Witkoff, it will create complications as he takes up his new job and will soon be negotiating with leaders of nations that are past, and potentially future, lenders to or buyers of his family real estate projects.”

In the end, for Trump and his cronies, it comes down to money. Witkoff may not have served on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee (right, that was the president Americans threw away) but there’s no question that he understands the stakes: Russia’s oil and gas. A few months ago, Politico reported that the Trump administration was debating whether to lift sanctions on Russia’s Nord Stream 2 natural gas pipeline and potentially other Russian assets in Europe, citing five sources familiar with the discussions.

“White House special envoy Steve Witkoff has been the main proponent of lifting sanctions, people familiar with the talks told POLITICO. Witkoff, who has said he has developed a friendship with Putin in his role as Trump’s envoy to Moscow, has directed his team to draw up a list of all of the energy sanctions that the United States has placed on Russia as part of the effort, two people familiar with the matter said.

“‘There is an internal White House debate between the energy dominance people — Burgum, who wants markets for U.S. LNG — and Witkoff, who wants to be closer to Russia,’ one of the people told POLITICO. Russia regaining its status as Europe’s top energy supplier would be “a bloodbath for American [oil and gas] producers,” this person continued.”

Russia researcher Olga Lautman writes: “As Trump continues to throw Ukraine under the bus, his allies are quietly working behind the scenes to reestablish U.S.-Russia financial ties. According to Bloomberg, Russian representatives have already begun discussing renewed energy cooperation, with state-controlled Gazprom reportedly in talks with American contacts.

“Trump’s goal isn’t peace—it’s restoring business deals with Russia and rehabilitating Putin on the world stage, all while giving Russia free rein in Ukraine and beyond. This is the same playbook as 2016: undermine U.S. alliances, weaken NATO, and enable Russia’s expansion but then we had guardrails.”

As India and China continue to buy Russian oil and gas, and Chinese companies fill the gaps left by departing U.S. corporations, Trump may have less and less leverage for any illusory “deal.”

And Witkoff? Compared to the Russians, he’s not such a tough guy after all. All he might be is the only friend the famously transactional and isolated Donald Trump has in the world.

Wow! What a convoluted web of...I don't know what. Whatever Witkoff's alleged Russian connections, Trump picked him as envoy, as Trump has done with the rest of his staff, for his loyalty, not his expertise. The picture that is gradually coming into focus, without ever becoming sharply defined, is that, in this world of shady billionaires, international corporations that control countries, money-laundering as a business model, and fuck-all-knows-what-else, Trump is a light-weight player and Putin may just buy and sell him as an afterthought.

Very very interesting Susan. Thanks so much for posting this fascinating piece that connects dots and leaves the reader wondering--